Movement and Thought: An Indispensable Pair

The relationship between movement and thought is a central topic in neuroscience and psychology. A fundamental question arises: does thought guide movement, or does movement influence thought? Recent research suggests that these two dimensions are inseparable and interact continuously in a dynamic process of adaptation and feedback.

The Interaction Between Movement and Thought

Have you heard of the Power Pose? Adopting an upright and open posture can increase self-confidence. Studies by Cuddy et al. (2010) have shown that such a posture influences hormone production by increasing testosterone levels while reducing cortisol, the stress hormone. One of the greatest marathon runners of all time, Eliud Kipchoge, employs a unique technique: he smiles during intense efforts to better manage pain and fatigue. Similarly, downhill skiers visualize every detail of their course before even starting their run, preparing both their body and mind for the effort ahead. These examples illustrate the profound connection between thought and movement. But does this influence work both ways?

Consider something as simple as walking. Studies indicate that an energetic and dynamic gait can enhance mood and reduce negative thoughts. Conversely, adopting a slouched posture and a slow pace can reinforce feelings of sadness or mental fatigue. Emotions also directly influence our movements. When we experience stress or anxiety, our muscles tense up, our breathing becomes shallow, and our movements grow more erratic. Conversely, a state of calm and serenity promotes smooth and relaxed gestures. Thus, movement and thought are deeply linked in a constant exchange, where one can modify the other and vice versa.

Thought Influences Movement

Neuroscientific studies reveal that our emotional states, intentions, and thought patterns alter our posture and actions. The way we conceptualize an action or goal directly affects motor execution and body posture. Mental visualization, for example, enhances the execution of a technical gesture. This technique is widely used in elite sports to reinforce movement efficiency and reduce uncertainty (Guillot & Collet, 2008). Stress also affects posture. A stressed individual tends to adopt a more closed posture, while a relaxed person stands more upright and at ease (Niedenthal, 2007). Stress directly impacts muscle rigidity and postural variability.

The connection between the motor cortex and motor learning plays a significant role in this process. Intention often precedes action. When we decide to move, our motor and premotor cortex prepare the movement execution. This principle underpins the embodied cognition model, which posits that our thinking guides our actions based on context and past experiences. An athlete who visualizes a movement before executing it improves their performance, as this process activates the same neural regions involved in actual movement execution. Cognitive processing of sensory information influences postural adaptation and decision-making in motion. Our perception of the environment modulates the way we engage in actions. In this perspective, movement is a consequence of thought and intention.

Movement Influences Thought

Conversely, the way we move shapes our perception, emotions, and cognition. Several theories in neuroscience suggest that motor experience profoundly structures cognitive mechanisms. Movement creates meaning. Neuroscientists such as Rizzolatti, who discovered mirror neurons, have demonstrated that movement influences cognitive abilities. Observing and imitating movements play a crucial role in learning and emotional regulation. Our motor patterns are embedded in the brain, influencing how we think, interact, and learn.

Historically, the brain developed to manage movement within the environment before it evolved into a center of reflection. According to researchers like Antonio Damasio and Daniel Wolpert, thought itself is an abstraction of movement, developed to anticipate and simulate future actions. Studies on motor disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease, reveal that a loss of fluid movement is often accompanied by cognitive impairments. In this view, thought is shaped by our motor experiences.

A Bidirectional Model: A Self-Adaptive System

Today, most neuroscientists agree that the relationship is bidirectional. Thought influences movement—emotional states and intentions shape our posture and actions. At the same time, movement influences thought—the way we move affects our emotions, perceptions, and decisions. In 2025, Volodalen®’s research team published the study ‘MIND TO MOVE: Differences in Running Biomechanics Between Sensing and Intuition Shod Runners.’ This was the first study to demonstrate the connection between cognitive processing and movement styles in a sporting context.

Motor Preferences: Fixed but Adaptable

Motor preferences™ are anchored in biology and neurophysiology—morphology, muscle chains, and motor development. However, they dynamically respond to internal constraints such as fatigue and stress, as well as external factors such as environment, surface, and equipment. They function as a self-adaptive system.

Available energy plays a role in adjustments. A decrease in energy can lead to compensatory strategies. For example, a Terrestrial profile athlete experiencing fatigue may recruit more posterior muscles to maintain efficiency. Context and environment also affect motor adaptation. The surface, equipment, or weather conditions can influence movement adjustments. A player’s psychological state, such as stress or confidence, can alter access to optimal motor patterns. Under pressure, an athlete may experience changes in their motor schemes.

The ultimate goal is optimized efficiency in alignment with body-mind intention. The body and mind continuously seek the most effective solution to respond to constraints while staying within the framework of motor preferences™. Intention guides action, and adaptability allows for optimizing motor responses without straying from the individual’s fundamental structure.

Volodalen® distinguishes itself through its innovative approach to motor preferences™, which integrates biomechanics, physiology, and psychomotricity. Motor Preferences Experts™ (MPE), the exclusive partner of Volodalen® in the USA, operates within the same framework and pursues the same objectives, ensuring that American athletes benefit from these advancements while advancing this field of research and application.

Volodalen®'s & MPE's Interventions

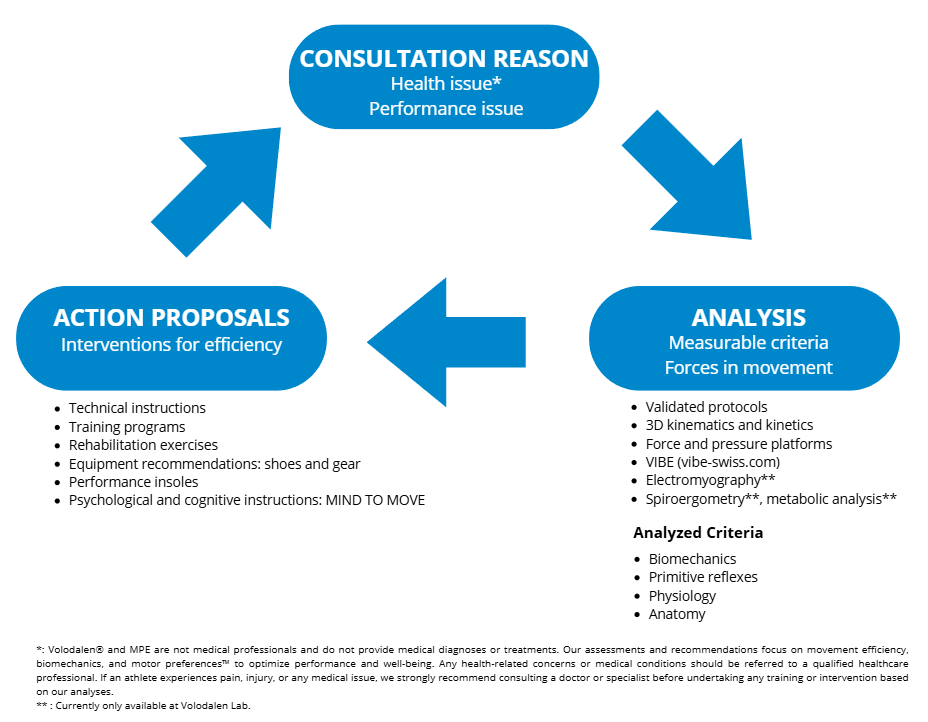

Based on an athlete’s consultation reason (whether a health or performance issue), Volodalen® & MPE rely on measurable criteria for analysis. We use validated protocols and advanced measurement tools to assess the athlete or patient. These analyses include anatomy, physiology, biomechanics, primitive reflexes, motor preferences™, and muscle chains. This thorough evaluation leads to concrete action plans to restore efficiency. Volodalen & MPE go beyond a simple movement analysis. Our approach encompasses:

- The optimization of sports performance.

- The adaptation of recovery and training.

- The integration of emotional and cognitive states into movement analysis.

- A holistic approach combining biomechanics, physiology, and movement psychology.

Conclusion

The debate over whether movement or thought takes precedence is akin to the classic dilemma of the chicken and the egg—there is no definitive answer, as they are interdependent. Human beings function as a continuous feedback system, where each movement generates new perceptions, and each thought shapes the way we move.

Volodalen®'s approach, applied by Motor Preferences Experts™, exemplifies this dynamic by integrating natural motor preferences®, biomechanics, physiology, and the influence of emotions and cognition on motor performance. By gaining a deeper understanding of this interaction, we can optimize performance, recovery, and injury prevention. Ultimately, the key to motor efficiency lies in recognizing and optimizing this movement-thought relationship, unlocking the full potential of both body and mind.

References:

- Berthoz, A. (1997). The Sense of Movement. Odile Jacob.

- Cuddy, A. J. C., Wilmuth, C. A., & Carney, D. R. (2010). The Benefit of Power Posing Before a High-Stakes Social Evaluation. Harvard Business School Working Paper, No. 13-027.

- Guillot, A., & Collet, C. (2008). Construction of the Motor Imagery Integrative Model in Sport: A Review and Theoretical Investigation of Motor Imagery Use. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 1(1), 31-44.

- Lussiana, T., et al. (2017). Similar Running Economy with Different Running Patterns Along the Aerial-Terrestrial Continuum. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 12, 481-489.

- Niedenthal, P. M. (2007). Embodying Emotion. Science, 316(5827), 1002-1005.

- Peper, E., Lin, I. M., Harvey, R., & Perez, J. (2017). How Posture Affects Memory Recall and Mood. Biofeedback, 45(2), 36-41.

- Ratey, J. J., & Loehr, J. E. (2011). The Positive Impact of Physical Activity on Cognition During Adulthood: A Review of Underlying Mechanisms, Evidence, and Recommendations. Reviews in the Neurosciences, 22(2), 171-185.

- Volodalen. (2023). E-Learning Reflexes and Preferences Level I. https://volodalen.com/formation/?formation=22

- Volodalen. (2023). Reflexion. https://www.reflexion-movement.com/en/ressources/volodalen.html